Is Competition a New Risk Factor in Morgan Stanley's World?

Clifford Asness, a Chicago Ph.D. as well as Managing and Founding Principle of AQR Capital Management, recently said that imitators are a new risk factor. Joe Nocera's August 18, 2007 New York Times article on quantitative investing reports his interviews:

In the view of several big-time quants I spoke to, their big mistake was in not realizing that their little corner of Wall Street had become so crowded with imitators — and that when others were forced to sell, they were going to get hurt. Now they are all trying to figure out how to factor that into their thinking for the future — Mr. Asness very much included. “We have a new risk factor in our world,” he said (bold inserted).

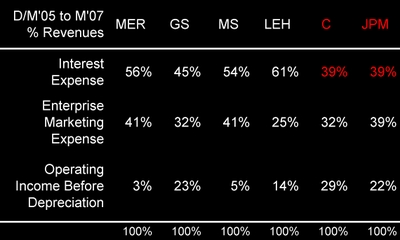

In case you are new here this is my 8th and final post in a current series on the competition for customers and capital among leading investment banks. In it I describe a model to factor competition into your thinking about pricing equities. Then I apply the model to Morgan Stanley (NYSE: MS) in a group containing three direct competitors: Goldman Sachs (NYSE: GS); Lehman Brothers (NYSE: LEH) and Merrill Lynch (NYSE: MER). For background and details see my book Competing for Customers and Capital.

FACTORING IN COMPETITION

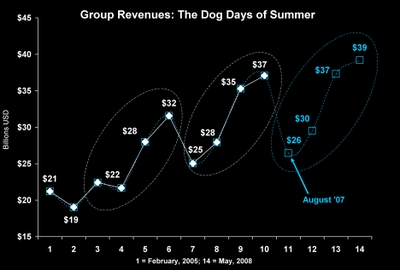

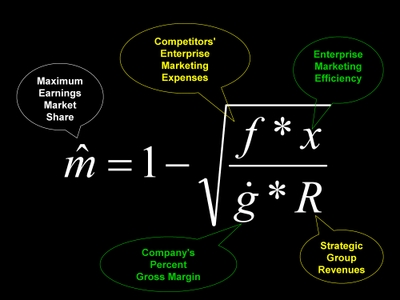

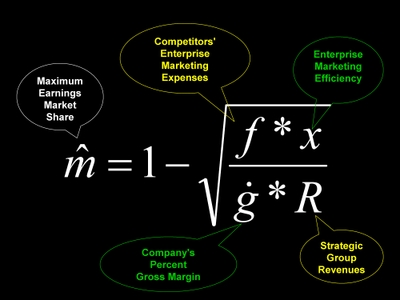

As you might expect, adding competition to a stock pricing model truly complicates the problem. Normally one would discount the projected future cash flow of a company. This approach won't do if you want to factor in the impact of competition. Put simply, competitors must be introduced in the very first step in the analysis and permitted to change the outcome in every other step through to the simultaneous pricing of their securities. This chart outlines my approach to factoring in competition.

1. The first step to factoring in competition is placing each company in a strategic group with others that share one or more customer segments and have access to similar resources. This makes it reasonable to pool their revenues.

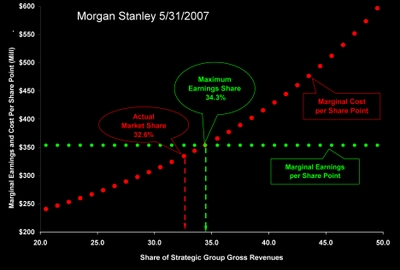

2. The next is to determine the degree to which management has maximized earnings within that group. Managers that maximize earnings achieve the greatest possible productivity using the resources they have. Companies that fall short of this goal suffer from lower relative earnings productivity. As the short-fall grows, investors become more likely to notice and discount the company's stock. As Al Rappaport said in his classic book Creating Shareholder Value:

It is … productivity that the stock market reacts to when pricing a company’s shares. Embedded in all shares is an implied long-term forecast about a company’s productivity – that is, its ability to create value in excess of the cost of producing it. When the stock market prices a company’s shares according to a belief that the company will be able to create value over the long term, it is attributing [this belief] to the company’s long-term productivity or, equivalently, a sustainable competitive advantage. In this way, productivity is the hinge on which both competitive advantage and shareholder value hang (Rappaport 1998, 69).

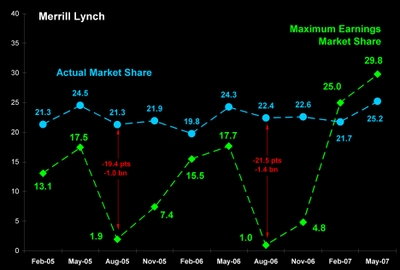

For a discussion of maximum earnings market share see my post "Double Bull's Eye for Morgan Stanley."

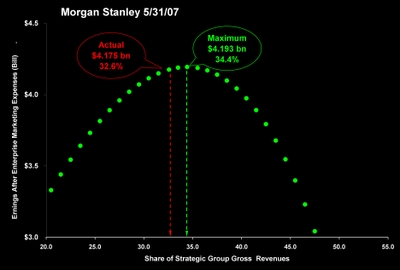

3. Calculate maximum earnings after enterprise marketing expenses. These expenses are reviewed in my post "Citigroup's Enterprise Marketing Expenses: The Middle Line."

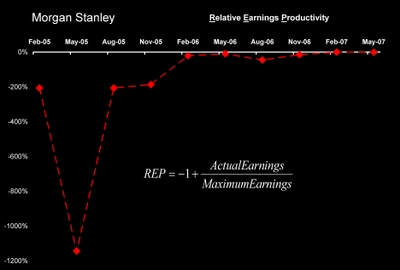

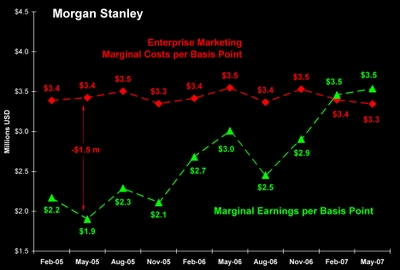

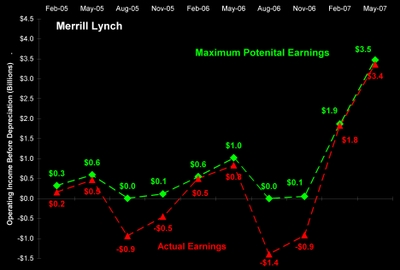

The difference between maximum and actual earnings is relative earnings productivity [REP]. The next chart documents Morgan Stanley's relative earnings productivity over the last ten quarters. After John Mack took the controls, the company marched steadily toward maximum earnings. By May, 2007 actual and maximum earnings were equal.

4. Next, quantify the interaction between a firm's performance in the product markets and stock market in which it operates. The value-sales differential is the basis of this calculation. For details see my Marketing Science Institute paper "Marketing's Impact on Firm Value: The Value-Sales Differential."

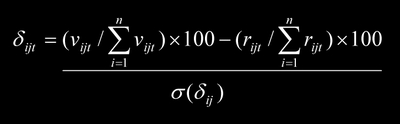

Value-sales differentials are adjusted for risk with a simple variation on the concept of risk-adjusted returns. First, subtract a company's share of revenues in product markets from its share of market value in a security market. Second, divide each of these differentials by their standard deviation. The result is a risk-adjusted differential, RAD or delta (i,j,t) in this equation:

The first term on the right-hand side is the share of value [SOV] created by firm i, in strategic group j, in time period t. The second term is the share of revenues [SOR] generated by the firm. The denominator, sigma, is the standard deviation in a time series of firm differentials. In my post on "Citigroup's Differentials: 3D Marketing Metrics" I applied the risk-adjusted differential to a strategic group of investment banks. Delta, or RAD, is a standard normal variable (with mean zero and standard deviation of one). Dropping the subscripts and summations above the equation becomes:

Since I assume that management maximizes earnings I add a “hat” to the SOR term and solve for SOV. The result is:

Think for a moment about the terms on the right-hand side of this equation. The first term is the firm's most recent risk-adjusted differential. This is multiplied by its enterprise marketing risk and added to maximum earning’s market share. Not only simple, it makes sense. When a company’s marketing risk is zero, the arithmetic product of RAD and Risk is zero. In this event share of value equals share of revenue. Of course, I must assume that maximum earnings market share is independent of the company's enterprise marketing risk. In my experience with over 100 applications of the model, this assumption holds.

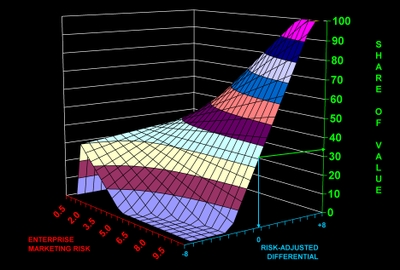

The next chart displays a plot of all possible shares of value at different levels of enterprise marketing risk and risk-adjusted differentials, for a maximum earnings market share of 34%. As this surface map shows, when RAD equals zero share of value equals share of revenue over all levels of risk.

When enterprise marketing risk increases, for a given maximum earnings market share, the company's share of value deviates more from share of revenue. And, as risk-adjusted differentials become more (or less) than zero, share of value again varies more (or less) from share of revenue. At the lowest level of risk in this chart (0.5), share of value ranges from a low of 30% at a RAD of -8 to a high of 38% with a RAD of +8.%. At the highest level of enterprise marketing risk in this chart (9.5), share of value ranges from 0% to 100%. For unit changes in risk-adjusted differentials, share of value increases (decreases) by the level of risk. For example, when risk is 5.0, share of value ranges from 0% to 74%. It does so in increments of 5 for every one unit change in risk-adjusted differentials.

5. Given an estimate of strategic group market value, this last equation converts share of value into stock price:

A firm's stock price equals its shave of value times the strategic group's market value divided by the number of shares outstanding.

PREDICTING MORGAN STANLEY STOCK PRICE

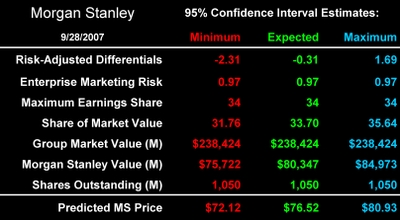

What will happen to Morgan Stanley's stock price the day after the release of its 3rd quarter report at the end of September, 2007? By way of illustration, the following table predicts its price using the competitive stock valuation model described above.

The company's enterprise marketing risk over the last ten quarters was 0.97. This is an extremely low risk. Which is why the stock price at either end of the 95% confidence interval does not vary much from the expected value. Morgan Stanley is in the tail of the risk distribution. The average enterprise marketing risk in my MSI study of 337 companies in 29 industries over ten years was 6.6.

Since I assume that management will, in fact, maximize earnings in the 3rd quarter with a 34% share of group revenues, only two questions remain.

First, what will be Morgan Stanley's risk-adjusted differential? It was -0.31 at the end of the second quarter, up from -1.65 in the 3rd quarter of 2006. I take this most recent observation as the best estimate of its expected value. Since RADs have a standard deviation of one, we can set lower (in red) and upper (in green) 95% confidence interval estimates around this expected value.

Second, what will be the market value of the group of four investment banks? In the current volatile market environment the best estimate is the group's value on Friday ($238.4 billion), since all the information up to that time already was factored into prices. From here on the rest is straight forward. I predict a low of price $72 and a high price of $81.

Morgan Stanley shares closed on Friday August 24, 2007 at $64.54 a share, giving it a market cap of $67.820 billion. The company's share of the group's value was 28.5%. If management maximizes earnings in the 3rd quarter, as it did in the 2nd, my model predicts investors will reward the company with a 33.7% share of the group's market value. The difference would amount to $12.5 billion or about an 18% premium over its closing value last Friday.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

Factoring in the effects of competition truly complicates the process of pricing securities. And certainly, my approach cannot be adapted to the performance of hedge funds without a lot of custom tailoring. But my hope is that it does suggest a way forward or at least food for thought about whether competition is indeed a new risk factor in Morgan Stanley's world, and yours.

A good friend of mine happens to be a financial economist. One day, a few years ago, while I was in the middle of writing my book I asked him what he thought about the working title: Competing for Customers and Capital. He said:

I know what you mean about the competition for customers, but I don't understand what you mean by the competition for capital. Capital markets are efficient; they're not imperfect like product markets.

What do you think?

Thanks for visiting.

~V